What Happened

Update: On February 7, Unleaded Kids and 12 other groups petitioned FDA to reconsider its action levels. On February 21, FDA filed the petition.

Two years ago, as part of its Closer to Zero program, FDA proposed action levels for lead in processed food intended for babies and children younger than 2 years of age (we’ll refer to them collectively as babies). On January 6, FDA finalized the proposal—essentially unchanged—by publishing guidance. Those final action levels are:

- 20 parts per billion (ppb) for dry infant cereals. FDA estimates that 91% of these products meet this limit.

- 20 ppb for single-ingredient root vegetables. FDA estimates that 88% of these products meet this limit.

- 10 ppb for other baby foods (subject to the exclusions below). FDA estimates that 97% of these products meet this limit. These products include fruits, vegetables, grain- and meat-based mixtures, yogurts, custards, puddings, and single-ingredient meats.

For comparison, in April 2023, the European Union (EU) established enforceable maximum levels—as opposed to FDA’s non-binding guidance1—of 20 ppb for “baby food and processed cereal-based food for infants and young children.”2

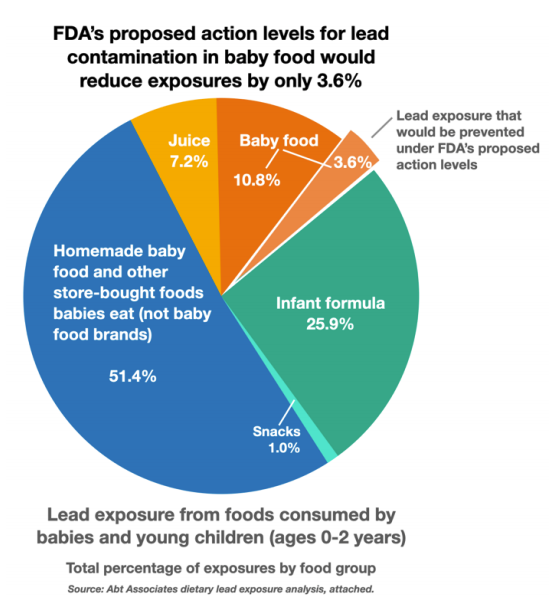

A Healthy Babies Bright Futures (HBBF) analysis shows that FDA’s proposed action levels would reduce lead exposure from covered baby foods by about one-quarter.3 However, those baby foods represent less than 15% of the total dietary lead exposure for babies, primarily because FDA exempts four major types of baby food from the action levels. Each exemption limits the potential benefits of the action levels.

Exemption 1: “Snack foods, including grain-based or freeze-dried snacks such as arrowroot cookies, puffs, rusks, and teething biscuits.”HBBF estimates that these snack food examples represent 1% of a babies’ overall dietary exposure to lead.

- The problem: Neither the guidance nor FDA’s rules define snack foods,4 and the examples fail to define what is not snack food. This failure effectively gives baby food companies the option to classify many of their products, such as purees, as snack foods. In the guidance, FDA indicates that it may develop an action level for grain-based snacks in the future after collecting more data, despite already having data showing that 98% of 92 samples of these products were below 20 ppb and 78% were below 10 ppb. For comparison, the EU does not exempt snack foods, so its maximum lead level is 20 ppb.5

Exemption 2: “Beverages, including toddler drinks.” HBBF estimates that juices represent about 7% of babies’ overall dietary exposure to lead. In April 2022, FDA proposed action levels of 10 ppb for apple juice and 20 ppb for other fruit and vegetable juices, and plans to finalize its decision in 2025.

- The problem: FDA has consistently missed its own deadlines for action. In addition, it appears to have no plans for beverages other than juices. For comparison, the EU’s maximum level for beverages for baby food is 20 ppb.6

Exemption 3: “Infant formula.” HBBF estimates that infant formula represents almost 26% of babies’ overall dietary exposure to lead.

- The problem: FDA did not explain the reasoning for the exemption. Presumably, the agency set lead limits as part of its review of those products, but Unleaded Kids found nothing in the rules.7 Through its Total Diet Study, FDA periodically finds lead in infant formula (both milk and soy). The most recent was in winter of 2019 when FDA found 10 ppb in a composite of three different milk-based powered formula products that it collected and reconstituted with distilled water. If the lead was only in one of those three products, the powder could have had more than 200 ppb.8 There are no indications that FDA investigated what caused the high level. For comparison, EU’s maximum level for powdered infant formula is 20 ppb and 10 ppb for liquid infant formula.9

Exemption 4: “Raw agricultural commodities”10 and “homemade foods such as fruit purees made at home.” HBBF estimates that homemade baby foods and other store-bought foods represent 51.4% of babies’ overall dietary exposure to lead.

- The problem: FDA’s guidance excludes a major source of exposure and has no plan to set action levels for them. For comparison, EU has maximum levels for virtually all raw agricultural commodities and food types, even for adults.11 In addition, many homemade foods made from store-bought produce may be more contaminated than baby food products with the same ingredients, according to another study by HBBF.

Why it Matters

As we explained in an October blog, babies are exposed to excessive amounts of lead (and cadmium) in their diet, according to a study by FDA scientists. The study focused on two groups: 1) infants 0-11 months who are not fed human milk; and 2) children 1-6 years. It found that 1 in 10 children in each age group consumed at least 2.4 microgram of lead per day (µg/day), exceeding FDA’s current interim reference level (IRL) of 2.2 µg/day. This means that more than 2.6 million children exceeded FDA’s target.

Our Take

At first glance, FDA’s action levels would appear more protective than EUs because it has an action level of 10 ppb instead of 20 ppb for the vast majority of baby foods covered. However, EU has action levels for all foods babies consume, including snack foods, beverages, infant formula, and raw agricultural commodities. In addition, some food companies may take EU’s enforceable maximum limits more seriously than FDA’s non-binding guidance.

In addition, FDA’s flawed definition of snack foods creates a loophole that companies can use to bypass the action levels it has set, further limiting the guidance’s impact. Rather than creating exemptions, it should be expanding the scope of the guidance to include more restrictive action levels, more types of food, and even prenatal vitamins, which would provide greater protection.

Looking more broadly at FDA’s Closer to Zero program, when FDA launched it in February 2021 in response to a scathing Congressional report, the agency planned to issue draft action levels for lead in baby food by April 2022 and finalize them by April 2024. It would release draft action levels for cadmium and arsenic in those foods by April 2024.

Unleaded Kids’ Tom Neltner cautiously supported the effort and identified areas for improvement. He thought the focus on baby food as an initial step was reasonable, especially when linked to a commitment to iteratively tighten the limits as industry makes progress in reducing the levels.

When FDA proposed the action levels for baby food, he applauded the draft guidance and submitted extensive comments that covered three key areas for improvement:

- Improve the draft action levels by more closely applying the criteria FDA described in the draft guidance;

- Improve the process that FDA uses to develop and communicate this and future action levels in its Closer to Zero Initiative; and

- Along with USDA and industry, encourage and invest in research to reduce lead in baby food.

Despite many thoughtful comments from stakeholders, FDA finalized the guidance with action levels unchanged and only updated the document with additional testing results from its lab. It made no apparent effort to leverage California’s law that accesses the data from baby food companies’ lab tests on every lot of baby food product made in 2024, effectively ignoring the best data to make decisions—and drive contamination closer to zero.

There is no reason for the agency to have taken two years to finalize the action levels unchanged. In doing so, FDA has ignored virtually all the comments it received without any explanation.

After four years, many missed deadlines, and unfulfilled commitments, FDA needs to fix its broken process and set meaningful standards to protect people from toxic elements in their food.

- The guidance states that “FDA’s guidance documents do not establish legally enforceable responsibilities.

Instead, guidances describe FDA’s current thinking on a topic and should be viewed only as recommendations, unless specific regulatory or statutory requirements are cited.” ↩︎ - See Section 3.1.26 in the regulation. ↩︎

- Because FDA did not change the proposed action levels, the HBBF analysis should still be accurate. ↩︎

- The food additive regulations at 21 C.F.R. § 170.3(n)(37) establishes snack foods as a category of foods stating “Snack foods, including chips, pretzels, and other novelty snacks.” Other sections describe snacks as including “candies and carbonated beverages.” ↩︎

- They are covered by Section 3.1.26 in the regulation. ↩︎

- They are covered by Section 3.1.25 in the regulation. ↩︎

- FDA’s infant formula rules address lead limits in two sections: 1) 21 C.F.R. § 106.40(e)(3) says “a manufacturer shall not reprocess or otherwise recondition an ingredient, container, or closure rejected because it is contaminated with microorganisms of public health significance or other contaminants, such as heavy metals; and 2) 21 C.F.R. § 106.20(f) requires that water in producing infant formula meet EPA’s drinking water limits. EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule does not have a maximum allowed level, rather its lead action level is 10 ppb. ↩︎

- 10 ppb X 3 X 7 since the 10 ppb was in the reconstituted composite of three products. The powder was reconstituted with seven times more water. ↩︎

- They are covered by Section 3.1.24 in the regulation. ↩︎

- The law at 21 U.S.C. § 321(r) defines this as any “food in its raw or natural state, including all fruits, that are washed, colored, or otherwise treated in their unpeeled natural form prior to marketing.” ↩︎

- They are covered by Section 3 in the regulation. ↩︎